Mitchell Hartman filed this Reporter’s Notebook for his Marketplace series “Help Not Wanted”

The first thing I did when I got the assignment to go to Chicago for a week of reporting on unemployment, was to call one of my oldest friends in the world. When we were little, we lived in the same crummy apartment building in East Rogers Park on Chicago’s North Side.

She’s all grown up now, owns a nice big apartment in Evanston, and has an executive-level job at one of Chicago’s premier academic hospitals. I asked her if she knew anyone who was unemployed. “Not really,” she said, after a long pause. “Not that I can think of, anyway.”

The next day, she called me back. She’d thought of some. Quite a few, actually. Two people in her building–both middle-aged professionals, out of work for months and months already. And then some parents at her kid’s school. Her colleagues at work knew a bunch as well.

The long-term unemployed were coming out of the woodwork.

And Illinois certainly has its share of them, with the 8th-highest unemployment in the nation. At 11.2 percent, it’s worse even than my struggling home state of Oregon.

Long-term unemployment a national trend

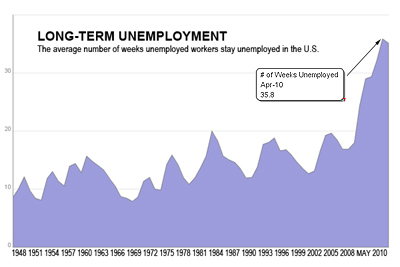

But really, we could have gone anywhere to find high, persistent unemployment. As one economist told me, long-term unemployment is now off the charts. Nearly half of unemployed people (46 percent) have been job-hunting for 27 weeks or more — the highest percentage since the Bureau of Labor Statistics began keeping track in 1948.

The typical job hunt is now 35 weeks — that’s more than eight months. Again, a record. There are five job-seekers for every available job. Before the recession it was less than two-to-one.

The effects of long-term unemployment

And unemployment–especially when it lasts a while — hits like a brick.

I’ve seen this in the parents at my kids’ school. We know high-tech workers, architects, urban planners, nurses, teachers, technical writers — all out of work for a year or more. In some families, both parents have lost jobs. I found the same pain — and shame — in the voices of middle-class workers I met in Chicago who have lost jobs and had no luck so far finding new ones.

One night around 2 a.m. I stumbled on a weird scene. As rain pelted down, spotlights shown on workers in hard hats hanging from struts a hundred feet in the air. They were upgrading a section of railroad bridge over the Chicago River. It seemed like hard, harsh work, and the hours were lousy. Several men came over and said it was pretty good, actually: the first construction jobs — the first jobs — they’d seen in over a year.

The youngest job-seekers are really taking it on the chin in this so-called “recovery.” I met a dozen graduates at Loyola University Chicago who are frankly freaked out at their job prospects. Most don’t have anything you’d call the on-ramp to a career lined up for the summer or fall. The lucky ones are working retail or behind the bar. At least they won’t have to sponge off their parents. Or they can’t. One told me whatever the job market holds, she’s “off the parental payroll” now.

Unemployment dreams and versus

I hit a rich vein when I asked them about their dreams — nightmares, really. One told me she dreamed she was a barista — but the espresso machine was in Brazil. And she didn’t speak Portuguese. People were yelling orders at her, and she couldn’t understand a word. Click on the audio links in the sidebar above to hear some more of those job dreams and unemployment nightmares.

If you have one, I’d love to hear it. You can post in in the comment section below.

At Columbia College in downtown Chicago, I found a scrappier scene — poetry students poetry — slamming at the school’s start-of-summer arts festival. I asked them to pen me some spontaneous verse about unemployment. Again, you can listen to what they came up with by clicking on the audio links above.

The new frugality

I got a tour of one 48-year-old woman’s rental apartment in the suburbs — a “frugality” tour, she called it. She showed me the fancy Vita-Mix juicer she bought — at Goodwill. The cashmere sweaters she got at a thrift store. The TV that doesn’t have cable anymore.

Earlier in her life she might have been ashamed at showing this new lifestyle to a stranger. But now she takes pride in it. After decades of paying her own way, putting herself through college, working hard and never being idle, she’s been unemployed for more than a year. She’s taken the opportunity to go back to school and get a Master’s in counseling. She now volunteers to help women at a domestic violence shelter prepare resumes and go out to look for work. But she hasn’t found any herself. And her unemployment’s about to run out.

I dropped in on a roomful of part-time sessional academics sipping tea and eating pastries at the Russian Tea Time restaurant downtown, as they were tutored by union organizers on the fine points of applying for unemployment benefits.

Many of them have been offered fewer classes to teach — and no summer work at all — because schools are cutting back. All have Master’s degrees or Ph.D.s. One told me she left a career in the insurance industry to teach writing because she thought an academic job would pay about the same and enrich her life more. But there aren’t many tenure-track jobs, and there’s a lot of competition.

A hard bounce back

There are those who say that if unemployed people really wanted to work badly enough, they’d find something — minimum-wage fast food or mowing lawns or odd jobs under the table. Some economists argue that the higher the unemployment benefits, and the more they’re extended, the less likely people are to feel the pain of true destitution and take whatever they can get.

And it’s true, people do hold out for something better when they’ve still got an unemployment check coming — even if it’s not nearly what they used to make and doesn’t pay the bills. But I wonder — should people take whatever they can get; settle for work that doesn’t pay a living wage; doesn’t interest, or stimulate, or inspire them in the least? That doesn’t utilize their education, or skills they’ve built up over years or decades? And that won’t likely lead them anywhere but to more low-wage monotonous work down the road?

Many of the long-term unemployed people I’ve met in my reporting are still holding out, still hoping for something better. Or at least for something halfway decent. They still seem to believe that’s what work is all about. But they’re running out of time.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.